MINERALS OF IGNEOUS

ROCKS

To correctly classify many igneous rocks it is first necessary to identify the constituent minerals that make up the rock. Piece of cake you say, I saw most of these minerals when I did the Minerals Exercise or I have them in my mineral collection. Well, its not quite that easy. The mineral grains in rocks often look a bit different than the larger mineral specimens you see in lab or museum collections. The following section is meant to assist you in recognizing common rock-forming minerals in igneous rocks. Refer back to it often as you attempt to classify your rock specimens.

To correctly classify many igneous rocks it is first necessary to identify the constituent minerals that make up the rock. Piece of cake you say, I saw most of these minerals when I did the Minerals Exercise or I have them in my mineral collection. Well, its not quite that easy. The mineral grains in rocks often look a bit different than the larger mineral specimens you see in lab or museum collections. The following section is meant to assist you in recognizing common rock-forming minerals in igneous rocks. Refer back to it often as you attempt to classify your rock specimens.

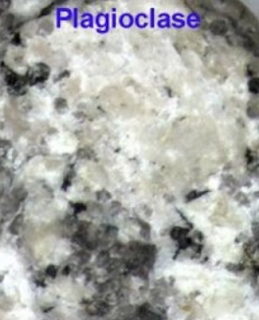

Plagioclase

Plagioclase is the most common mineral in igneous rocks. The illustration to the left shows a large chalky white grain of plagioclase. The chalky appearance is a result of weathering of plagioclase to clay and this can often be used to aid in identification. Most plagioclase appears frosty white to gray-white in igneous rocks, but in gabbro it can be dark gray to blue-gray. If you examine plagioclase with a hand lens or binocular microscope you can often see the stair-step like cleavage and possibly striations (parallel grooves) on some cleavage faces. Some potassium feldspar is white like plagioclase, but is usually a safe bet to identify any frosty white grains in igneous rocks as plagioclase. Expect to find plagioclase in most phaneritic igneous rocks and often as phenocryts in aphanitic rocks.

Quartz: the dark gray, glassy grain is quartz.

Quartz

Plagioclase is the most common mineral in igneous rocks. The illustration to the left shows a large chalky white grain of plagioclase. The chalky appearance is a result of weathering of plagioclase to clay and this can often be used to aid in identification. Most plagioclase appears frosty white to gray-white in igneous rocks, but in gabbro it can be dark gray to blue-gray. If you examine plagioclase with a hand lens or binocular microscope you can often see the stair-step like cleavage and possibly striations (parallel grooves) on some cleavage faces. Some potassium feldspar is white like plagioclase, but is usually a safe bet to identify any frosty white grains in igneous rocks as plagioclase. Expect to find plagioclase in most phaneritic igneous rocks and often as phenocryts in aphanitic rocks.

Quartz: the dark gray, glassy grain is quartz.

Quartz

Quartz is also a very common mineral in

some igneous rocks. It can be difficult to

recognize since it doesn't look like the

beautiful, clear hexagonal-shaped mineral

we see in mineral collections or for sale in

rock shops. In igneous rocks it is often

medium to dark gray and has a rather

amorphous shape. If you look at it with a

hand lens you will notice the glassy

appearance and lack of any smooth

cleavage surfaces. You will also find

quartz grains resist scratching with a nail

or pocket knife, You can expect to find

abundant quartz in granite and as

phenocryts in the volcanic rock rhyolite.

In some other common igneous rocks

you may find a few scattered grains of

quartz, but it is often conspicuous by its

absence. Once recognized, quartz is

rarely confused with any other common

rock-forming mineral.

Orthoclase: the slightly pinkish grains are the potassium feldspar, orthoclase.

Potassium Feldspar

Orthoclase: the slightly pinkish grains are the potassium feldspar, orthoclase.

Potassium Feldspar

Think pink is the motto for potassium feldspar. The image to the left shows several large grains of the potassium feldspar, orthoclase; note the pinkish cast. As orthoclase is a feldspar, you should also see the stair-step cleavage characteristic of feldspars. Unfortunately, all potassium feldspar is not pink, microcline is usually white. How does one distinguish white potassium feldspar from plagioclase? The answer is that in hand samples it is nearly impossible. Sometimes striations on cleavage faces allow you to differentiate the two. Plagioclase has striations, potassium feldspar does not. But in most cases any white feldspar is identified as plagioclase and any pink feldspar as orthoclase. Expect to find orthoclase as a common constituent of granite and matrix material in rhyolite. In the latter rock the orthoclase is too fine-grained to be seen even with a binocular microscope, but its presence gives most rhyolites a distinct pinkish cast.

Muscovite

Muscovite is not a common mineral in igneous rocks, but rather an accessory that occurs in small amounts. It is shiny and silvery, but oxidizes to look almost golden. In fact, more prospectors probably confused muscovite in their pans for gold than they did pyrite (fool's gold). Muscovite has excellent cleavage and will scratch easily. If you suspect muscovite is present, try taking a nail to it. It should flake off the rock. Muscovite occurs in some granites and occasionally in diorite. Unlike, its close cousin, biotite, it rarely occurs as phenocrysts in volcanic rocks.

Biotite: the small, black grains are biotite.

Biotite

Biotite occurs in small amounts in many igneous rocks. It is black, shiny and often occurs in small hexagonal (6-sided) books. Unfortunately, it is often confused with amphibole and pyroxene. Like muscovite, it is soft and has good cleavage. Try scratching the black grains with a nail or knife. Biotite will flake off easily. Biotite is differentiated from amphibole by shape of the crystals (hexagonal for biotite and elongated or needle-like for amphibole) and by hardness (biotite is soft, amphibole is hard). It is differentiated from pyroxene by hardness, color (biotite is black and pyroxene dark green) and occurrence (biotite is found in light-colored igneous rocks like granites, diorites and rhyolites while pyroxene occurs in dark-colored rocks like gabbro and basalt). Expect to find biotite as a common accessory in granite, and as phenocrysts in some rhyolites.

Muscovite is not a common mineral in igneous rocks, but rather an accessory that occurs in small amounts. It is shiny and silvery, but oxidizes to look almost golden. In fact, more prospectors probably confused muscovite in their pans for gold than they did pyrite (fool's gold). Muscovite has excellent cleavage and will scratch easily. If you suspect muscovite is present, try taking a nail to it. It should flake off the rock. Muscovite occurs in some granites and occasionally in diorite. Unlike, its close cousin, biotite, it rarely occurs as phenocrysts in volcanic rocks.

Biotite: the small, black grains are biotite.

Biotite

Biotite occurs in small amounts in many igneous rocks. It is black, shiny and often occurs in small hexagonal (6-sided) books. Unfortunately, it is often confused with amphibole and pyroxene. Like muscovite, it is soft and has good cleavage. Try scratching the black grains with a nail or knife. Biotite will flake off easily. Biotite is differentiated from amphibole by shape of the crystals (hexagonal for biotite and elongated or needle-like for amphibole) and by hardness (biotite is soft, amphibole is hard). It is differentiated from pyroxene by hardness, color (biotite is black and pyroxene dark green) and occurrence (biotite is found in light-colored igneous rocks like granites, diorites and rhyolites while pyroxene occurs in dark-colored rocks like gabbro and basalt). Expect to find biotite as a common accessory in granite, and as phenocrysts in some rhyolites.

Amphibole

Amphibole is a rather common mineral in all igneous rocks, however, it is only abundant in the intermediate igneous rocks. It occurs as slender needle-like crystals (see image to the left). It has good cleavage in 2 directions and hence has a stair- step appearance under a binocular microscope. It is often confused with biotite and pyroxene. Biotite is softer and the needle-like crystals differentiate it from pyroxene. One caution, most students believe that all amphibole crystals must have the pencil- like appearance. Remember the orientation of grains in an igneous rock is random. What would your pencil look like if you looked at it down the eraser? Not all grains of amphibole will be oriented so you can see the elongation of the crystals. Its a good guess that if you see a few crystals that have the "classic" amphibole shape, the other black grains are also amphibole. Biotite and amphibole do occur together in igneous rocks, but the association is not all that common. Amphibole is very commom in diorite, less so in granite or gabbro. It also is a common and diagnostic phenocryst in andesite.

Pyroxene: the equi-dimensional, green grains are pyroxene.

Pyroxene

Amphibole is a rather common mineral in all igneous rocks, however, it is only abundant in the intermediate igneous rocks. It occurs as slender needle-like crystals (see image to the left). It has good cleavage in 2 directions and hence has a stair- step appearance under a binocular microscope. It is often confused with biotite and pyroxene. Biotite is softer and the needle-like crystals differentiate it from pyroxene. One caution, most students believe that all amphibole crystals must have the pencil- like appearance. Remember the orientation of grains in an igneous rock is random. What would your pencil look like if you looked at it down the eraser? Not all grains of amphibole will be oriented so you can see the elongation of the crystals. Its a good guess that if you see a few crystals that have the "classic" amphibole shape, the other black grains are also amphibole. Biotite and amphibole do occur together in igneous rocks, but the association is not all that common. Amphibole is very commom in diorite, less so in granite or gabbro. It also is a common and diagnostic phenocryst in andesite.

Pyroxene: the equi-dimensional, green grains are pyroxene.

Pyroxene

Pyroxene is common only in mafic igneous rocks. It occurs as short, stubby, dark green crystals (see image to the left). It has poor cleavage in 2 directions and cleavage surfaces are often hard to see with even a binocular microscope. It is often confused with biotite and amphibole. Biotite is softer, darker and occurs in predominantly light-colored rocks Amphibole is also darker and occurs in needle-like crystals rather than the stubby shape of pyroxene. Association is the best guide for the identification of pyroexene. It is usually restricted to dark-colored rocks (the image on the left is of pyroxene is a very rare light-colored rock called shonkenite) such as gabbro or basalt.

Olivine

Olivine is common only in ultramafic igneous rocks like dunite and peridotite. It occurs as small, light green, glassy crystals (see image to the left). It has no cleavage. The texture of olivine in igneous rocks is often termed sugary. Run your fingers over the grains, do they feel like sandpaper? The mineral is most probably olivine. Although olivine occurs in gabbro and basalt, it is far more common in peridotite and dunite. Because of the light green color and sugary texture it is rarely confuded with other rock-forming minerals.

Olivine is common only in ultramafic igneous rocks like dunite and peridotite. It occurs as small, light green, glassy crystals (see image to the left). It has no cleavage. The texture of olivine in igneous rocks is often termed sugary. Run your fingers over the grains, do they feel like sandpaper? The mineral is most probably olivine. Although olivine occurs in gabbro and basalt, it is far more common in peridotite and dunite. Because of the light green color and sugary texture it is rarely confuded with other rock-forming minerals.